Hard-to-Reach Energy Users

Synopsis

There is a significant percentage of the human population (we estimate over 2/3 of energy users fall into it!) who can be regarded as “hard-to-reach energy users”. These are the people policymakers, utility programme managers and research experts are struggling to engage with – often, for good reason. Their barriers are often related to (dis)trust, stigma, shame or fear, which is why it is important to identify and engage trusted messengers or ‘navigators’, usually, from the community or frontline services. This very large energy user segment was the focus of Phase 1 of the HTR Task.

In Phase 2, we pursue two main purposes:

- To build on Phase 1 and examine the underlying causes (rather than just the symptoms) for energy injustice, as to ensure a “fair, orderly and equitable energy transition” (COP28) for all

- To focus on “hidden” energy users, which includes those living in hidden hardship, those who choose to remain hidden on purpose, and those who are hidden because they are deprioritised by policy makers and programme managers.

Overview

Task Duration:

Phase 1:

June 2019 to May 2022 (1 year extension to October 2023)

Participating countries:

New Zealand, Sweden, United States of America

Phase 2:

November 2023 to October 2026

Participating countries:

New Zealand, Sweden, United States of America

Contact:

For more information on the Task, please contact Dr Sea Rotmann drsearotmann@gmail.com

Latest From Hard-to-Reach Energy Users

Summary insights from the recent HTR Task workshop elevating Indigenous voices

On June 6, 2024, we held a National Expert workshop for the Hard-to-Reach Energy Users Task, as part of the Users TCP Executive Committee and Consortium for Energy Efficiency (CEE) board meetings in Boston.

Industry-funded research into customers living in hidden hardship inspires Phase 2 of HTR Task

The two largest electricity retailers in Aotearoa New Zealand, Mercury and Genesis Energy funded HTR Task Leader Dr Sea Rotmann to research customers living in hidden hardship. The industry wanted to work alongside the community to find more effective solutions to the problem of engaging hard-to-reach energy users.

Final Country Report of Phase 1 HTR Task: United States

This is the final report deliverable to conclude Phase 1 of our HTR Task, with special focus on our U.S. funder and National Expert, the Consortium for Energy Efficiency.

Hard-to-Reach Energy Users Publications

HTR Task Summary of National Expert Workshop in Boston (June 2024)

These are the summary meeting minutes from the Hard-to-Reach Energy Users Task hui (workshop) in Boston (June 6, 2024). We focused on elevating Indigenous voices, who are top priority communities to involve in the just energy transition efforts in the three countries participating in the HTR Task.

Research into hard-to-reach electricity customers living in hidden hardship

This report presents the conclusions of a two-year project, co-funded by the two largest electricity retailers in Aotearoa New Zealand. Industry wanted to work alongside the community to find

Final Country Report HTR Task: United States

This is the final report deliverable to conclude Phase 1 of our HTR Task, with special focus on our U.S. funder and National Expert, the Consortium for Energy Efficiency. We

Subtasks & Deliverables

Introduction to the ‘hard-to-reach’ energy users

Many of our behaviour change and demand response interventions concentrate on the uptake of energy-efficient technologies in developed countries and so-called “green consumption” efforts. Much of our focus is on technology choice per se, with a lot less on the cognitive, motivational and contextual factors that are affecting those choices. Relatively speaking, behavioural-oriented policy initiatives are rather limited, and often confined to experimental settings, and utility-driven programmes. In fact, policy efforts addressing behavioural anomalies explicitly, are the exception. This has led to the continued energy efficiency gap – the difference between the cost-minimising level of energy efficiency and the level of energy efficiency actually realised.

In addition, so-called “Behaviour Changers” (those agencies or individuals tasked to change energy user behaviours via policies, programmes or pilots) often have a blind spot when it comes to tackling the most difficult audiences – like HTR energy users. Too often they literally disappear into what can only be called the “too-hard basket”. This is of particular concern when tackling the global energy crisis, and transitioning our energy system. To actually achieve a truly “just, orderly and equitable transition”, we need to ensure that the majority of energy users who are hard-to-reach, or completely hidden (for whatever reason), are prioritised when designing behavioural or demand response interventions and decarbonisation initiatives.

What defines a “hard-to-reach” energy user?

As there are many different, sometimes conflicting definitions of what constitutes a “hard-to-reach” energy user (see Rotmann et al, 2020), we have co-created this broad working definition as a starting point for our research:

“In this Task, a hard-to-reach energy user is any energy user from the residential and non-residential sectors, who uses any type of energy or fuel, and who is typically either hard-to-reach physically, underserved, or hard to engage or motivate in behaviour change, energy efficiency and demand response interventions that are intended to serve our mutual needs.”

Note: Our mutual needs pertains to not just fulfilling e.g. regulatory requirements or government policy directives, but also increasing demand for energy services and the (often only implied) needs of the HTR audience. The audience needs (e.g. equitable access to affordable energy, healthy homes) may sometimes conflict with government or utility needs (e.g. reducing energy use, competition for customers, electrification).

What are our shared goals for this Task?

“Our shared goal (for Phase 1) is to identify, define, and prioritise HTR audiences; and design, measure and share effective strategies to engage those audiences to achieve energy, demand response and climate targets while meeting access, equity, and energy service needs.”

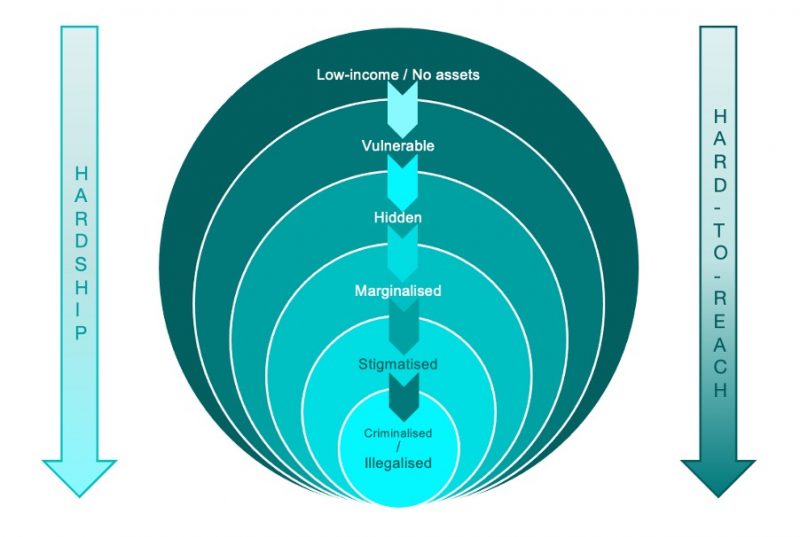

Note: Equity here means expanding all programmes and policies to ensure the inclusion and facilitate the participation of individuals in vulnerable or underserved communities, such as isolated elderly, single parents, Indigenous and geographically remote people, as well as criminalised or illegalised groups such as the homeless, drug addicts, or overstayers. Instead of leaving them suffer in hidden hardship, we hope to elevate these groups to be regarded as priority communities to ensure a truly just energy transition.

“Our shared goal (for Phase 2) is to identify, listen to, elevate, and empower priority voices*, so as to be guided by their experiences, insights, and needs, to achieve a truly just energy system transition for all. The just transition should build energy sovereignty, influence and resilience in those priority communities.

Note: Priority voices and communities are those who are currently hidden, missed, underserved or intentionally underinvested in by decision-makers. Examples are marginalised / forgotten (e.g., the disabled, remote Indigenous), stigmatised / ostracised (e.g., refugees, ethnic minorities, welfare recipients), and/or illegalised / criminalised (e.g., the homeless, people suffering from substance abuse) groups, but also hidden groups in the commercial sector (e.g., home-based microbusinesses), the “squeezed middle” (with mid-high incomes but no assets), and those households with total high energy consumption where only a single bill payer is known (e.g., student flatters, overcrowded households). These examples are not exhaustive.

The predecessor of this work called Task 24: Behaviour Change in DSM – Phase I and Phase II showed, over an 8-year research period, how to successfully apply behaviour change interventions both in theory and practice. Rather than picking a specific disciplinary approach or model of understanding behaviour, the Task showed that facilitating multi-stakeholder collaboration and visualising the socio-ecology of a given energy system could lead to highly successful behavioural interventions. What this Task also showed, however, is that most interventions focused on generic audiences, like “households”. They often failed in defining detailed audience profiles based on their relevant contexts, barriers and needs. In addition, there was limited identification which specific behaviours could and should actually best changed, by whom, in what way, and how to measure impact and successful outcomes for end users and a variety of stakeholders.

Phase I of the HTR Task focused on a very distinctive audience segment, the hard-to-reach (HTR) energy users, and how to better motivate and engage them in energy efficiency and demand-side interventions geared at changing specific energy-using behaviours. It is important to recognise that the best outcome for these audiences is often not energy-saving per se, but an improvement in health and wellbeing.

Work Completed

During Phase 1 of the HTR Task, participating country experts and the Task Leader:

● Fielded a Qualtrics survey with 120 responses from HTR practitioners and researchers in over 20 countries, including 39 CEE member organisation responses.

● Conducted in-depth interviews with almost 50 practitioners on better engaging underserved energy users in Sweden, the U.S./CAN, UK, and NZ.

● Developed 19 case studies from 8 countries (U.S., Canada, Sweden, New Zealand, Portugal, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom). Analysed the extent to which these case study examples adhered to best behavioural social science programme and evaluation practices through a cross-country comparative analysis.

● Held three international workshops to share international learnings, including in the U.S. in 2019, France (for Sweden) in 2022, and Aotearoa New Zealand in 2023.

● Established an informal network of practitioners, policy-makers, and researchers aiming to better address energy hardship and vulnerability across the globe.

● Published two scientific publications, one book, eleven conference papers, and twenty technical reports and white papers, all linked to in the Appendix.

● Presented at 4 webinars, developed two training programmes, and were invited onto 5 government expert groups and conference steering committees.

What We Learned

Summary main findings from this collaboration to date include:

● Fostering and rebuilding trust is essential when dealing with HTR energy users. Building trusted relationships with multiple stakeholders is crucial, particularly those community and frontline providers directly serving the target audience.

● Identifying and training trusted middle actors benefits programmes. These “navigators” are already present and trusted in the community and understand what the lived experiences and needs of their community are.

● Cost-effectiveness hurdles can be mitigated by starting with a subset of the target audience.

● Psychographic data and qualitative insights are an important complement to demographic and quantitative data, and should be collected before designing interventions.

● Co-design of programmes and interventions is a key best practice. Ideally, trusted community actors should be trained (and paid!) to deliver the programmes as well.

● Strength-based (or “mana-enhancing”) approaches can be highly beneficial when engaging Indigenous communities by identifying, recognising, and reinforcing existing skills, interests, and capacity within those communities.

● Scaling up necessitates confirming that messages will resonate with new audiences, or in different contexts.

● Targeting messaging through communication channels that the target audience already utilises is efficient and effective.

● Language barriers may seem easier to rectify than other barriers, but language barriers are often enmeshed with cultural barriers. Cultural competence of staff is just as important – if not more so – than linguistic competence.

● Pilots that do not have specific energy savings targets themselves (e.g. because they focus on wellbeing), but allow for extensive exploration of the approaches that may be likely to spur future energy savings, can still benefit energy efficiency targets down the road.

● Evaluation merits additional attention. While 84% of programmes from our cross-country analysis defined a specific behaviour intended to change, only 10% evaluated whether behaviour change had occurred.

Overarching Objectives of Phase 2

Research Questions

Phase 1 Research Questions and Findings

Process Research Question: Can the Toolbox for Behaviour Changers developed by Task 24 be used to support better interventions targeted at HTR energy users?

Answer: Yes, clearly. We have since further developed and field-tested the Building Blocks of Behaviour Change Framework (Karlin et al, 2021) and Behaviour Changer Framework 2.0 (Rotmann & Weber, forthcoming).

Audience Research Questions: Who are main HTR energy users in each participating country? How can they be defined and described? How materially are these HTR segments underserved?

Answer: We have identified, described and characterised, in-depth, HTR energy users from expert interviews and surveys (Ashby et al, 2020a&b), and from over 1000 publications, in a literature review (Rotmann et al, 2020). They are all materially underserved, but to varying extent. For example, low-income households are relatively easy to identify and target with programmes, policies and interventions. The more compounding and intersecting vulnerabilities they endure, the harder-to-reach they become (see diagram below). Renters and landlords (residential and commercial) are extremely HTR, and for very different reasons. Socially-marginalised/stigmatised/criminalised groups and SMEs are very likely the hardest-to-reach, and most underserved energy users, especially on the extremely-diverse small business end (70% of commercial businesses).

Audience Size Research Questions: Based on country statistics and expert opinions, what is the approximate, estimated size of the HTR user group in each participating country? Based on implemented pilots and case studies in each participating country, what is the potential effectiveness (or effect size) that one can expect from behavioural-oriented policy or programme intervention on this group?

Answer: Based on all of our research (but especially our HTR literature review; Rotmann et al, 2020), we believe that this group is extremely large and entails at least 2/3 of all energy users. These estimated numbers are increasing rapidly with the global energy (poverty) crisis. For example, in the UK there are estimates that up to 2/3 of households will fall into energy hardship by the end of this year!

Engagement Strategy Research Questions: What type of policy and behaviour change programmes have the potential to motivate and engage HTR users to use energy more effectively and efficiently? What is the level of public acceptability of such policy interventions in each participating country? What are the ethical challenges associated with them?

Answer: Our Year 2 Case Study Analyses and the international research overview into energy hardship recently prepared for Aotearoa’s Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment (Rotmann, 2022) delve deeply into best practice interventions and their challenges. Clearly the most important strategy is to engage trusted Middle Actors (especially from the community or frontline services) to help identify, recruit and engage vulnerable HTR energy users (in the residential sector). However, it needs to be acknowledged that these Middle Actors are also extremely hard-to-reach, and that building these trusted relationships and networks takes time, and involves a lot of humility, listening and empathy rather than approaching them with fixed ideas or top-down engagement strategies and interventions that aren’t fit-for-purpose.

Field Pilot Research Question: Can we use field research pilots to prove that a robust, internationally-validated, standardised process for behavioural interventions on the HTR is a better approach than the current, scatter-shot one?

Answer: Yes. We have already completed several field research pilots in Aotearoa New Zealand (Rotmann & Cheetham, 2023; Rotmann, 2024), the US (see our work with Uplight and See Change Institute) and Canada (Rotmann & Karlin, 2019; Rotmann et al, 2024), and our research process has been used highly-successfully to date (e.g. Rotmann & Karlin, 2021; Karlin et al, 2022; Mundaca et al, 2023).

Phase 2 Research Questions

- What steps are currently being taken towards a just energy transition? Who are the main actors? Which interventions have worked and which haven’t?

- What have been some unintended consequences of well-intentioned efforts to more equitably engage priority audiences? Under what circumstances have efforts towards more equitable engagement in reality had the opposite impact? What lessons can be learned to avoid this scenario in the future?

- Who are HTR energy users who choose to remain / are purposefully hidden from / by authorities designing interventions aimed at addressing the energy crisis, and/or are living in hidden hardship?

- Who are the navigators and intermediaries who have trusted relationships with those energy users and how can we improve our methodologies and approaches to engagement with them?

- What are the cultural / country differences and similarities when identifying and engaging hidden energy users in the field? What are general recommendations for taking these differences and similarities into account when addressing energy injustice and furthering a just energy transition?

Methodology

Behavioural Socio-Ecology

Our broad disciplinary approach will continue to be behavioural socio-ecology, taking a whole systems view of the complex interactions and relationships between the environment, utility industry, infrastructure, technology, politics, services, and hidden energy users and their communities.

Collaborations and trusted relationships

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Technology Collaboration Programmes (TCPs) highlight, in their name, the importance of research and technology collaborations. Over 6000 scientists partake in the 38 TCPs. We have utilised and built on these networks over 12+ years of research in this Task. Our specific focus will be on building trusted relationships with community and frontline navigators, especially Indigenous stakeholders, and those looking after marginalised and underserved energy users who live in hidden hardship, or who otherwise remain hidden – this also includes high-income energy users, and SMEs.

Our research process

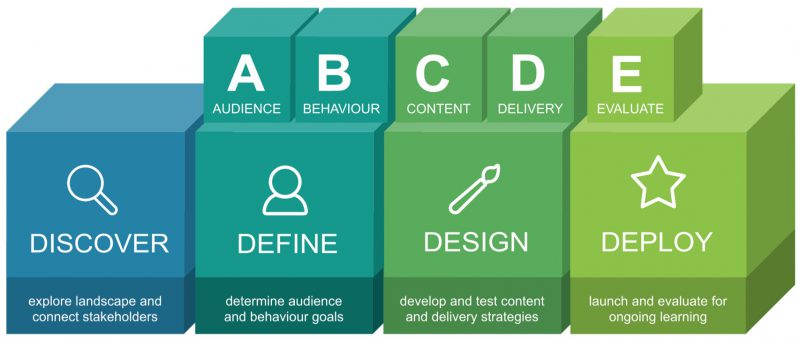

Our Project Partner See Change Institute (SCI) has developed a process to identify and test programme variables as the “ABCDE building blocks of behaviour change”. This process is aimed at helping Behaviour Changers better design, implement, and evaluate such programmes. We will adapt it, as needed, for our priority audiences, stakeholders and contexts. This process, which we have utilised for ex-post case study analyses and field-tested in research pilots, contains the following elements:

Diagram of the “Building Blocks of Behaviour Change” Research Process

To summarise our research process (see diagram above): Each phase includes both qualitative and quantitative research to marry inductive and deductive strategies of learning.

First, the overarching, shared programme or policy goals are discovered in the context of the existing landscape of work and the mandates of key stakeholders. Second, the target audience and behaviours are defined through mixed-methods customer research and modelling. Then, the interventions can be designed to address specific audience and behavioural needs and key content and delivery variables can be “pretotyped” via experimental and usability testing. Finally, once the intervention has been optimised based on empirical data, it can be deployed and evaluated in a pilot study, using both process and impact evaluation to determine not only whether it worked but how it can be continuously improved over time.

Storytelling

Storytelling will continue to be our overarching language and method of ‘translation’ between different countries, sectors, and disciplinary jargons. We will continue to explore the power of storytelling in its many forms, as outlined in our 2015 eceee summer study paper and our highly-cited Special Issue in Energy Research and Social Sciences called ‘Storytelling and narratives in energy and climate change research’ (see Rotmann, 2017). Task 24 has also published an ‘A-Z of storytelling’ report (Rotmann, 2018).

Benefits for Participants

Benefits for Behaviour Changers and co-funders to join this Task

Opportunities for Global Networking and Co-creation

- Participating countries only get to shape the direction and focus of this global research collaboration.

- They become part of, and gain access to the combined HTR expert platform encompassing 100s of experts from different countries, research disciplines and sectors (including national and local government, utilities, community groups, academia, health, commercial, industrial, transport, education etc.).

- They gain access to, and participate in cross-country case study comparisons on their chosen priority research areas via the highly-reputable IEA Technology Collaboration Programme (TCP) network.

- They gain access to, and participate in the User-Centred Energy Systems Academy including ability to disseminate their case studies and field pilots in promoted webinars, peer-reviewed publications and technical reports.

- It helps them to reduce duplication of efforts by learning from success stories on engaging the HTR in other sectors or jurisdictions.

Access to Cutting-Edge Tools and Resources

- Learn from and share global best practice in facilitating multi-stakeholder collaboration and co-creation on how to better reach the hard-to-reach.

- This includes community outreach and engagement, which requires empathy and cultural sensitivity (training) to build trusted long-term relationships and find hidden energy users.

- Get access to a global network of experts in behavioural science and energy justice.

- Get expert facilitation and backbone support to design, implement and evaluate field research pilots.

Dissemination & Relationships

• Final Country Report HTR Task Phase 1: United States. DOI10.47568/3XR129

• eceee column by Dr. Sea Rotmann: How to Reach the Hard-to-Reach?

Energy Hardship E-Newsletter by Aotearoa’s Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment (December 2021). Announced HTR Task Leader’s appointment to Energy Hardship Reference Group and our Case Study Analysis and Webinar.

Phase 2 – Just Energy Transition Landscape & Stakeholder Assessment

Phase 1 – Case Study Analyses and Cross-Country Case Study Comparison

- Rotmann, S., Mundaca, L., Ashby, K., O’Sullivan, K., Karlin, B. and H. Forster (2021). Subtask 2: Case Study Analysis Methodology Template for National and Contributing Experts. HTR Task Users TCP: Wellington. https://doi.org/10.47568/3OR111

- Rotmann, S. (2021). Case Study Analysis – Aotearoa New Zealand. HTR Task Users TCP: Wellington. 70pp. https://doi.org/10.47568/3XR112

- Mundaca, L. (2021). Case Study Analysis – Sweden. HTR Task Users TCP: Lund. 34pp. https://doi.org/10.47568/3XR116

- Ashby, K. (2021). Case Study Analysis – U.S. and Canada. HTR Task Users TCP: Boston. 41pp. https://doi.org/10.47568/3XR118

- Butler, D. (2021). Case Study Analysis – United Kingdom. HTR Task Users TCP: London. 79pp. https://doi.org/10.47568/3XR117

- Sequeira, M.M., Gouveia, J.P. and P. Palma (2021). Case Study Analysis – Portugal. HTR Task Users TCP: Lisbon. 38pp. https://doi.org/10.47568/3XR115

- Feenstra, M. (2021). Case Study Analysis – the Netherlands. HTR Task Users TCP: Delft. 19pp. https://doi.org/10.47568/3XR114

- Realini, A., Maggiore S. and Varvesi, M. (2021). Case Study Analysis – Italy. HTR Task Users TCP: Milan. 18pp. https://doi.org/10.47568/3XR113

- Feenstra M., Middlemiss L., Hesselman M., Straver K., S. Tirado Herrero (2021). Humanising the Energy Transition: Towards a National Policy on Energy Poverty in the Netherlands. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3: 31. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/frsc.2021.645624

- Mundaca, L., Rotmann, S., Ashby, K., Karlin, B., Butler, D., Macias Sequeira, M., Pedro Gouveia, J., Palma, P., Realini, A., Maggiore, S., and M. Feenstra (2023). Hard-to-Reach Energy Users: An empirical cross-country evaluation of behavioural-oriented programmes. Energy Research and Social Science 104:103205.

Phase 2 – Characterisation & audience segmentation of hidden energy users

Phase 1 – HTR Definition, Literature & Stakeholder Review on Audience Characterisation

- Ambrose A., Baker W., Batty E. and A McNair Hawkins (2019). “I have a panic attack when I pick up the phone”: experiences of energy advice amongst ‘hard to reach’ energy users. People, Place and Policy, Early View, 1-7.

- Ambrose A., Baker W., Batty E. and A McNair Hawkins (2019). Reaching the ‘Hardest to Reach’ with energy advice: final report. Sheffield Hallam University: Sheffield.

- Ashby, K., Smith, J., Rotmann, S., Mundaca, L. and A. Ambrose (2020a). HTR Characterisation. HTR Task Users TCP by IEA: Wellington. https://doi.org/10.47568/3XR102

- Ashby, K., Rotmann, S., Smith, J., Mundaca, L., Reyes, J., Ambrose, A., Borelli, S. and M. Talwar (2020b). Who are Hard-to-Reach energy users? Segments, barriers and approaches to engage them. ACEEE Summer Study for Energy Efficiency in Buildings. Proceedings: Monterey. https://doi.org/10.47568/3CP103

- Sequeira, M.M., Gouveia, J.P., de Melo, J.J. (2024). (Dis)comfortably numb in energy transitions: Gauging residential hard-to-reach energy users in the European Union. Energy Research & Social Science 115: 103612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2024.103612

BEHAVE 2021 Conference proceedings (all extended abstracts below can be found in there):

- Ashby, K., Rotmann, S. and L. Mundaca (2021). A collaborative international approach to characterising hard-to-reach energy users. BEHAVE 2021 Conference Proceedings.

- Chester, M., Karlin, B. and S. Rotmann (2021). A gap analysis of the literature on energy-saving behaviours in the commercial sector. BEHAVE 2021 Conference Proceedings.

- Rotmann, S., Ambrose, A., O’Sullivan, K., Karlin, B., Forster, H., and L. Mundaca (2021). To what extent has COVID-19 impacted hard-to-reach energy users? BEHAVE 2021 Conference Proceedings.

- Rotmann, S., Mundaca, L., Ambrose, A., O’Sullivan, K. and K.V. Ashby (2021). An in-depth review of the literature on hard-to-reach energy users. BEHAVE 2021 Conference Proceedings.

eceee Summer Study 2021:

- Rotmann, S., Ambrose, A., Chambers, J., Mundaca, L., O’Sullivan, K., Viggers, H., Helen Clark, I., Karlin, B. and H. Forster (2021). To what extent has COVID-19 impacted hard-to-reach energy users? eceee Summer Study online proceedings.

- Rotmann, S., Ambrose, A., Chambers, J., Mundaca, L., O’Sullivan, K., Viggers, H., Helen Clark, I., Karlin, B. and H. Forster (2021). To what extent has COVID-19 impacted hard-to-reach energy users? eceee Summer Study online proceedings.

Literature Review

Phase 2 – Updating our research approach with an equity lens

Phase 1 – Our research process: The Building Blocks of Behaviour Change

- Karlin, B., Forster, H., Chapman, D., Sheats, J., and Rotmann, S. (2021). The Building Blocks of Behavior Change: A Scientific Approach to Optimizing Impact. The See Change Institute: Los Angeles.

- Karlin, B., Rotmann, S., Ashby, K., Mundaca, L., Butler, D., Sequeira, M.M., Gouveia, J.P., Palma, P., Realini, A. and S. Maggiore (2022). Process matters: Assessing the use of behavioural science methods in applied behavioural programmes. eceee Summer Study Proceedings: Hyéres.

Phase 2 – Co-design of engagement strategies for chosen target audiences

Phase 2 – Field Research & Pilots

- Rotmann (2024). Research into hard-to-reach customers living in hidden hardship. SEA – Sustainable Energy Advice Ltd: Pūponga. 25pp.

- Here is a short video from the report launch.

Phase 1 – Field Research Pilots

North American field research for utility and software clients

- Rotmann, S. and B. Karlin (2020). Training commercial energy users in behavior change: A case study. ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings: Monterey. https://doi.org/10.47568/3CP104

- Uplight (2021). Bridging the Gap: Driving Energy Customer Action. Uplight Research Series: 21pp.

- Rotmann, S., Cowan, K. and H. Forster (2021). Uplight Customer Engagement Research: Qualitative Insights from Focus Groups On Energy Management Activities in the MUSH Sector. Client Report, See Change Institute: 109pp.

- Uplight (2021). Getting to Yes with Municipalities, Universities, Schools and Hospitals. Research into the MUSH Sector (partnered with See Change Institute). Boulder, Colorado: 26pp.

- Rotmann, S., Hibbert, C., Ward, D. and B. Karlin (2022). Uplight SMB Research: How to better engage SMB customers with rate offering and tools. Client Report, See Change Institute: 29pp.

- Uplight (2022). Six Reasons Why Most SMBs Don’t Switch Rates. Research into the SMB Sector (partnered with See Change Institute). Boulder, Colorado: 21pp.

- Rotmann, S., Karlin, B. and K. Cowan (2024). Energy Behaviour: Considerations for Standardization. Standards Research on behalf of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA). CSA, Toronto: 51pp.

Aotearoa NZ field research funded by utilities and the government

- Rotmann, S. & V. Cowan (2022). Piloting Home Energy Assessment Toolkit (HEAT Kits) to empower hard-to-reach energy users. eceee Summer Study Proceedings: Hyéres.

- Rotmann, S. (2022). EnergyMate Phase 3 Evaluation. Client Report for Energy Retailers Association New Zealand (ERANZ). SEA – Sustainable Energy Advice Ltd, Wellington: 42pp.

- Rotmann, S. & Cheetham, E. (2022). Hidden Hardship Hui Report. Client Report for Mercury and Genesis Energy. SEA – Sustainable Energy Advice Ltd, Wellington: 23pp.

- Rotmann, S. & Cheetham, E. (2023). Hidden Hardship Hui #2 Report. Client Report for Mercury and Genesis Energy. SEA – Sustainable Energy Advice Ltd, Wellington: 28pp.

- Rotmann, S. (2023). Hidden Hardship Hui #3 Report. Client Report for Mercury and Genesis Energy. SEA – Sustainable Energy Advice Ltd, Wellington: 16pp.

- Rotmann, S. (2022). Memo to Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment (MBIE) summarising international research on energy hardship programmes. SEA – Sustainable Energy Advice Ltd, Wellington: 6pp.

- This research includes an online database of 68 energy hardship programmes and interventions in 4 regions (North America, EU, UK and Australia).

- Rotmann, S. and V. Cowan (2022). Piloting Home Energy Assessment Toolkits (HEAT kits) to empower hard-to-reach energy users. eceee Summer Study Proceedings: Hyéres.

- Rotmann, S. and E. Cheetham (2023). Home Energy Assessment Tool (HEAT Kits) for Whānau. Final Report for the Support for Energy Education in Communities (SEEC) Fund. SEA – Sustainable Energy Advice Ltd, Puponga: 66pp.

- Rotmann, S. and E. Cheetham (2023). Successfully reaching the HTR by improving Home Energy Assessment Toolkits with the help of community and frontline providers. BEHAVE Conference Proceedings: 632-643.

- Rotmann, S. (2023). The dangers of calling hidden and underserved energy users hard-to-reach. BEHAVE Conference Proceedings: 644:655